1964 Visionary Thoughts

In October 1964, Reginald G. Haggar wrote to the Pottery Gazette and Glass Trade Review with his visionary thoughts about preserving a traditional old potbank for the benefit of future generations.The editor of the Gazette wrote in ‘Topics’ on page 1083

"In our news pages Mr. Reginald Haggar, well-known author and artist, makes an impassioned plea for preservation of the historical Potteries in the form of bottle ovens (“beautiful”) and even a whole factory as a complete industrial museum. Those of us who love the area with all its character and idiosyncrasies would back his plea, and hope that something can be done to preserve the old, whilst acknowledging the benefit of modern methods in present-day production of the Six Towns."

|

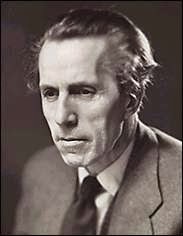

| Reginald G. Haggar (1905-1988) |

A letter to The Pottery Gazette and Glass Trade Review - PRESERVING POTTERIES HISTORY

"Sir — The Potteries, as some of us knew it 30 years ago, is fast disappearing. The distinctive architecture of the Potteries towns, the bottle oven, is almost a thing of the past. The two or three thousand which existed then are now reduced to a couple of hundred or less, and, of these, not more than a score are still in operation.

It does not seem to be realised what beautiful things these bottle ovens were, the astonishing variety of contour, the queer and unusual bulges that resulted from the excess of heat, the varied manner of construction, the shaping of the neck and the almost battlemented edge. Some were heavily corseted, others still graceful spinsterish affairs which seemed so virginal as never to have trafficked with clay or fire.

You might come across a large nest of them at a street corner, or perhaps a lone slender cone at the end of a backyard. Now most of these have gone and the atmosphere is the cleaner and healthier for it.

For many years some of us have been urging the preservation not merely of an oven or two but of a whole factory which might be renovated and transformed into a live Potteries industrial museum and in which it might be possible for future generations to see how pots were made and decorated and fired in the days of Astbury and Whieldon and Wedgwood and Spode.

There they would see some of the original machines and tools and equipment. They would see also the astonishing variety of Potteries products, for in such a museum with its original warehouses it would be possible to display on a generous scale the prototypes of industry, moulds, models and machinery, and unusual pieces. One room might be used to house one example of every article made in this so diversified an industry.

Familiar things like the vessels comprised by dinner, breakfast and tea services would be there (and they run into thousands) but so too would many unfamiliar objects: the bell pulls, doorplates, key escutcheons and door knobs made by specialists in door furniture, the trinket sets that formerly adorned the dressing table and the toilet services for the obsolescent wash-tables, galley pots, whose name take us back to foreign trade in medieval times, creel steps and shuttle eyes made for Manchester cotton spinners. marbles and taws for children and parlour bowls for Victorian grown ups, nest eggs for poultry farmers, porcelain teeth, ceramic buttons, and a thousand other things.

At such a museum it would be possible to trace the history of tea drinking and all the weird and wonderful patents for brewing tea in a teapot, or the evolution of electrical equipment or the development of the water closet.

An old factory transformed into a live museum, that is the idea and year by year one sees the disappearance of desirable factories. Some have gone almost overnight: the factory at Longport with its original Georgian house; the Victoria works at Fenton which was worked by Miles Mason when he abandoned trade as a Chinaman and the adjoining house where he lived; the great ovens and workshops of the old Bedford Works at Shelton where, if it had been preserved, it might have been possible to moor a long boat gay with castles and roses and all its equipment; the factory at Greenhead, Burslem; and so on.

One great factory still survives more or less intact as far as its façade is concerned, although. I believe the ovens are no more, the factory which Josiah Wedgwood built by the canal in the valley between Burslem, Hanley and Newcastle. The scene today is grim: then, with its village of workers’ houses, its little inn and the master's house it must have been rather fine, a prototype for an industrial settlement.

At Etruria, industrial and social history are enshrined. There is another eighteenth century factory at Cobridge, a smaller but not less attractive one, with its original bell turret and many surviving old workshops.

At Longton there is a derelict factory of great age, the Pelican works I believe it is called, which holds the eye because of its diminutive scale. It stands at the end of Sutherland Road and its original entrance was at the corner where a draper’s shop now stands. A long low building on shelving ground so that from one side it scans even lower than it is, and above the roofs poke the broad mouths of the hungry ovens. Broken windows afford glimpses of decay and dereliction which the imagination changes into a flurry of human activity.

Further along are the great bastilles of the Industrial Revolution, the great gaunt factories built on shordrucks, and above them higher still the lordly ovens flaunting their curves over the rooftops. Longton is still relatively full of history.

It is still not too late, therefore, to preserve something of the history of this great industry for future generations. Cannot something be done about it before the landmarks of the Industrial Revolution disappear or decay beyond repair?"

It does not seem to be realised what beautiful things these bottle ovens were, the astonishing variety of contour, the queer and unusual bulges that resulted from the excess of heat, the varied manner of construction, the shaping of the neck and the almost battlemented edge. Some were heavily corseted, others still graceful spinsterish affairs which seemed so virginal as never to have trafficked with clay or fire.

You might come across a large nest of them at a street corner, or perhaps a lone slender cone at the end of a backyard. Now most of these have gone and the atmosphere is the cleaner and healthier for it.

For many years some of us have been urging the preservation not merely of an oven or two but of a whole factory which might be renovated and transformed into a live Potteries industrial museum and in which it might be possible for future generations to see how pots were made and decorated and fired in the days of Astbury and Whieldon and Wedgwood and Spode.

There they would see some of the original machines and tools and equipment. They would see also the astonishing variety of Potteries products, for in such a museum with its original warehouses it would be possible to display on a generous scale the prototypes of industry, moulds, models and machinery, and unusual pieces. One room might be used to house one example of every article made in this so diversified an industry.

|

| Gladstone Works - Moulds in the mould makers shop |

Familiar things like the vessels comprised by dinner, breakfast and tea services would be there (and they run into thousands) but so too would many unfamiliar objects: the bell pulls, doorplates, key escutcheons and door knobs made by specialists in door furniture, the trinket sets that formerly adorned the dressing table and the toilet services for the obsolescent wash-tables, galley pots, whose name take us back to foreign trade in medieval times, creel steps and shuttle eyes made for Manchester cotton spinners. marbles and taws for children and parlour bowls for Victorian grown ups, nest eggs for poultry farmers, porcelain teeth, ceramic buttons, and a thousand other things.

At such a museum it would be possible to trace the history of tea drinking and all the weird and wonderful patents for brewing tea in a teapot, or the evolution of electrical equipment or the development of the water closet.

|

| Gladstone Works - Reginald G Haggar, watercolour |

An old factory transformed into a live museum, that is the idea and year by year one sees the disappearance of desirable factories. Some have gone almost overnight: the factory at Longport with its original Georgian house; the Victoria works at Fenton which was worked by Miles Mason when he abandoned trade as a Chinaman and the adjoining house where he lived; the great ovens and workshops of the old Bedford Works at Shelton where, if it had been preserved, it might have been possible to moor a long boat gay with castles and roses and all its equipment; the factory at Greenhead, Burslem; and so on.

One great factory still survives more or less intact as far as its façade is concerned, although. I believe the ovens are no more, the factory which Josiah Wedgwood built by the canal in the valley between Burslem, Hanley and Newcastle. The scene today is grim: then, with its village of workers’ houses, its little inn and the master's house it must have been rather fine, a prototype for an industrial settlement.

At Etruria, industrial and social history are enshrined. There is another eighteenth century factory at Cobridge, a smaller but not less attractive one, with its original bell turret and many surviving old workshops.

At Longton there is a derelict factory of great age, the Pelican works I believe it is called, which holds the eye because of its diminutive scale. It stands at the end of Sutherland Road and its original entrance was at the corner where a draper’s shop now stands. A long low building on shelving ground so that from one side it scans even lower than it is, and above the roofs poke the broad mouths of the hungry ovens. Broken windows afford glimpses of decay and dereliction which the imagination changes into a flurry of human activity.

|

| Gladstone China 1972, pre-museum |

Further along are the great bastilles of the Industrial Revolution, the great gaunt factories built on shordrucks, and above them higher still the lordly ovens flaunting their curves over the rooftops. Longton is still relatively full of history.

It is still not too late, therefore, to preserve something of the history of this great industry for future generations. Cannot something be done about it before the landmarks of the Industrial Revolution disappear or decay beyond repair?"

Reginald G. Haggar, October 1964

|

| Reginald G. Haggar, water colour. Sutherland Road, Longton Private Collection |

1965 More Visionary Thoughts

On 9th April 1965 Reginald Haggar wrote a piece for the Evening Sentinel'CITY SHOULD PRESERVE BEST OF OLD BUILDINGS'

This is scan of the Sentinel piece. Unfortunately the right hand edge was cut off sometime in its past.Transcript of part:

Evening Sentinel, Friday April 9th, 1965

City should preserve best of old buildings

An exhaustive survey of Stoke-on-Trent’s industrial archaeology was advocated by Mr. Reginald Haggar during a lecture at Shelton last night. The survey should be undertaken swiftly to see what was worth preserving and how the buildings, if preserved, could play a useful - spiritual as well as utilitarian - part in the city’s future life.

“Let me say that this kind of survey would have a specific end in view - the preservation of worthwhile and potentially viable fabrics” explained Mr Haggar. “Among the things which might be preserved,” he suggested, “were factory facades, bottle ovens, inns, shops, chapels, canals, bridges, railway stations and tunnels.”

Mr Haggar continued “Why should these things be preserved, and remember, I have said they cannot and should not be preserved unless they can be integrated effectively into the life of the 20th century?” He went on, “Because from the ways and habits and modes of living and working in the past we may learn lessons of how to live together and work together in the present and the future.”

“Because when we look back on the buildings of our past we are reminded, if only faintly, of what they went through and suffered in order that we might survive. Because out of such darkness and dirt so much beauty, sheer beauty, was created.

~~~~

Reginald George Haggar (1905–1988) R.I., A.R.C.A., F.R.S.A. was a significant British ceramic designer. He was born in Ipswich and studied at Ipswich School of Art and the Royal College of Art. In 1929, he became assistant designer at Minton's pottery in Stoke-on-Trent, rising to art director six months later, a post he held until 1939. Working in water colours and ceramics, his designs reflected both the radical and lyrical elements of the Art Deco style.

After leaving Minton, he became Master-in-Charge of the Stoke School of Art to 1941 and then of Burslem School of Art until 1945. He was an artist and lecturer in the Potteries area. He painted many pictures of North Staffordshire.

|

| Reginald G. Haggar, pencil and wash. Locketts Lane, Longton 1970 |

|

| Reginald G. Haggar exhibiting one of his paintings at The City Museum and Art Gallery, (now Potteries Museum and Art Gallery), Stoke. |